Q: What kind of pens do you use for sketches and inking? And also, what kind of paper works best for you?

I get variations on this question fairly frequently, and before I answer, I want to make the point that there are no “right” tools. When I was a kid, I was convinced that certain mysterious, elusive art supplies were the key to drawing like my cartooning idols. I was greatly disappointed when, after great effort and expense, I finally procured a Winsor & Newton sable hair brush or a Hunt 102 nib and my drawings still looked like shit. For the most part, I recommend experimenting and finding the tools that produce the best results for you, even if they’re not the ones listed in a “how to draw comics” book or on some guy’s Substack newsletter.

I would also like to make a brief pitch on behalf of cheap tools. There are a number of art supplies that are considered cartooning staples, and are often name-checked by some of our greatest practitioners. I understand the appeal of some of these things, but I can tell you that there was a period of my life where I became overly obsessive about my artwork, and part of that was due to the fact that the supplies I was using were so damn expensive. (The other part is just low-grade OCD.) This was around the time I was working on the last chapter of my book Shortcomings. I became preoccupied with making each page “perfect,” and my pace slowed to less than a page per week. When I finally finished that book, I made a decision to throw out most of my art supplies and start from scratch, gravitating towards the cheapest, most readily-available materials. I drew the story “Killing and Dying” using only stuff I could buy at the local Rite Aid: printer paper, a felt tip pen (for the lettering), and a mechanical pencil (for everything else). And not to be overly dramatic here, but it was kind of liberating. If a panel wasn’t going the way I wanted, I just crumpled up the paper and started over. Being freed from the anxiety of making a perfect page with the “right” tools allowed me to focus more on the actual writing and cartooning, which is really all that matters.

Having said that, here’s the tools that are currently sitting beside my drafting board. They’re the ones I’ve used for my recent New Yorker covers, as well as my book The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist.

Muji Low Center Gravity mechanical pencil

Uni 0.5 mm mint blue Nano Dia lead

I use this pencil and lead for all my preparatory drawing. I like the light blue lead because it doesn’t reproduce in the scanning / printing process, so I don’t have to erase after inking. But be forewarned: the pencil lines tend to fade fairly quickly. I’m not sure if it’s just a chemical reaction with the air or if it has to do with the friction of moving your hand over it as you draw, but I would recommend moving on to the inking right away.

Tombow Mono Zero eraser

Pentel Clic Eraser

Watch out for the plastic stick embedded in the end of the Tombow eraser. If you’re not paying attention, you can wear the eraser down to that point and end up scratching your artwork in a way that not only damages your drawing but also the surface of the paper.

Tachikawa “school” nibs

Tachikawa T-25 nib holder

These are great pens and nibs from Japan, but they’re pretty easy to find in the U.S. This particular nib is nice and firm, but with just a little bit of “give” for line width variation. A dip pen is probably the most antiquated tool I use, but I love it—not just for the line it produces, but also because it makes me feel like a real cartoonist. I used this pen for all the drawing in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist.

Faber-Castell PITT artist pen, sizes XS, S, F, and M

For about 20 years, I was a devoted Rapidograph pen user, and then at a certain point I just got sick of dealing with them. They’re great when they’re working properly, but all the fuss of cleaning them, refilling them, having them clog right when I need them...I just got tired of it. So I started using these disposable pens instead, for things like panel borders and lettering. And I actually like them better. Unlike a Rapidograph, these have a little bit of “give,” so depending on how hard you push down on them, you can get a little bit of line width variation. I think it’s made my lettering look a little softer and more lively.

(And yes, I know that’s the whole point of Rapidographs: that they deliver a steady, even line. I’m not criticizing them for that, just saying that I personally prefer the slight pressure response from the PITT pens. Everybody calm down, especially you fanatical Rapidograph devotees.)

Winsor & Newton series 7 brush (size 3)

Okay, this is the one expensive, snooty, old-fashioned cartoonist tool that I still rely on. There’s a reason why so many cartoonists use this for inking: it’s dependable, versatile, and if you take care of it and keep it clean, it can last a long time. I use this for the thicker, more expressive lines in my New Yorker covers, and for filling in black areas. If you use a slightly textured paper, you can control the roughness of the line with varying amounts of ink.

Dr. Ph. Martin’s ink, either TECH or Black Star

I’m not actually sure that the black TECH ink is still available. I ordered a bunch of large bottles of the stuff years ago, and I’m still using it. But the “hi-carb” Black Star ink is a perfectly good substitute.

Muji correction pen

By far the best, most reliable “white-out” pen. For some reason, this one doesn’t clog the way most others do, and the paint is perfect for inking over.

Dr. Ph. Martin’s Bleed Proof White

This is basically just white paint that I can apply with a brush. It allows more accuracy and texture than a correction pen, and it can create a nice rough edge for certain effects. But beware: it’s water-soluble so don’t try to ink over it.

Oh, and in terms of paper, I don’t have a super strong endorsement. The paper that I used for the first fifteen years or so of my career has been unpredictable recently, and I’ve had repeated problems with bleeding—where I’ll go to ink a page that I’ve spent days penciling and the ink flares out on the paper, almost like it was damp. So I’m still searching for the perfect alternative. For my most recent New Yorker covers, I used Canson Montval watercolor paper, 140 lb., cold press. For The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, I used a brand of paper that I will not identify here by name. It’s affordable, widely-available, and it worked very well for my purposes, but I just can’t bring myself to endorse the comics-related name and branding. If you’ve seen it, you probably know what I’m talking about.

Q: Your work has changed a great deal over the years (not just from when you started but much later too). Is this largely just the byproduct of doing more and more work or do you consciously take steps to improve / grow through the work or in between work? If so, how? To me, it seems like there was huge development in the look of your work in around 2010 or thereabouts. I’m most curious about that. If you agree that there was a change then, what would you say was the reason for it?

For a long stretch of my early career, I think any kind of evolution in my work was really just a struggle for competency. I started self-publishing my comics when I was sixteen, and once I realized that those comics were actually being read by strangers out in the world, I felt like I was drowning while simultaneously learning how to swim. I knew that my work was being recognized for some sort of superficial proficiency—I wasn’t bad for my age—but I certainly didn’t have the experience, the vision, or the training to create the kind of work I aspired to. I was thoroughly dissatisfied with what I was producing, and I became obsessed (probably to an unhealthy degree) with making it, uh…less dissatisfying.

Unfortunately, this multi-year, hit-or-miss learning process played out in full view to the public, with each step published as an issue of Optic Nerve. (Drawn & Quarterly took over the publishing reins in 1995, exposing my work to an even wider audience.) I attempted a number of ill-advised stylistic experiments, and the blatant influence of various cartoonists popped up with uncomfortable frequency. I was trying to tell stories in those early comics, but more importantly, I think I was trying to teach myself how to do it better.

The period that you refer to, around 2010, coincides with something I wrote about earlier in this post. I had just completed the final chapter of Shortcomings, and after working in that precise, exacting mode for nearly five years, I was eager to find a new way of making comics. I wanted to work quicker, and more importantly, I wanted to find a way back to the sense of fun and discovery I had when cartooning was just a hobby.

Part of that process was as simple as throwing out my art supplies and starting fresh. But that idea of clearing the decks also applied to how I approached writing and drawing comics, the kinds of stories I wanted to tell, even the kinds of characters I was going to focus on. Prior to Killing and Dying, I had largely stuck to the old edict of “write what you know,” focusing mainly on semi-autobiographical stories, or at least, stories that took place (literally and figuratively) in the very small world that I inhabited. My challenge to myself with Killing and Dying was to create characters and stories that were outside of my own direct experience, to allow each story to have its own distinct tone, and to create each story (in terms of writing process, art style, art supplies, etc.) in a totally different way. I worried that this would result in a formless, seemingly random collection, but I think to some degree the stories were all unified by my subconscious, my aesthetics, and the limits and quirks of my drawing ability.

And just to clarify, I didn’t complete Killing and Dying and think, “Ah…mission accomplished!” I was still dissatisfied with the results, but I felt like I’d moved the needle, so to speak. At very least, I knew I had changed my methods, and for the first time in a while, the process of making comics felt new and exciting.

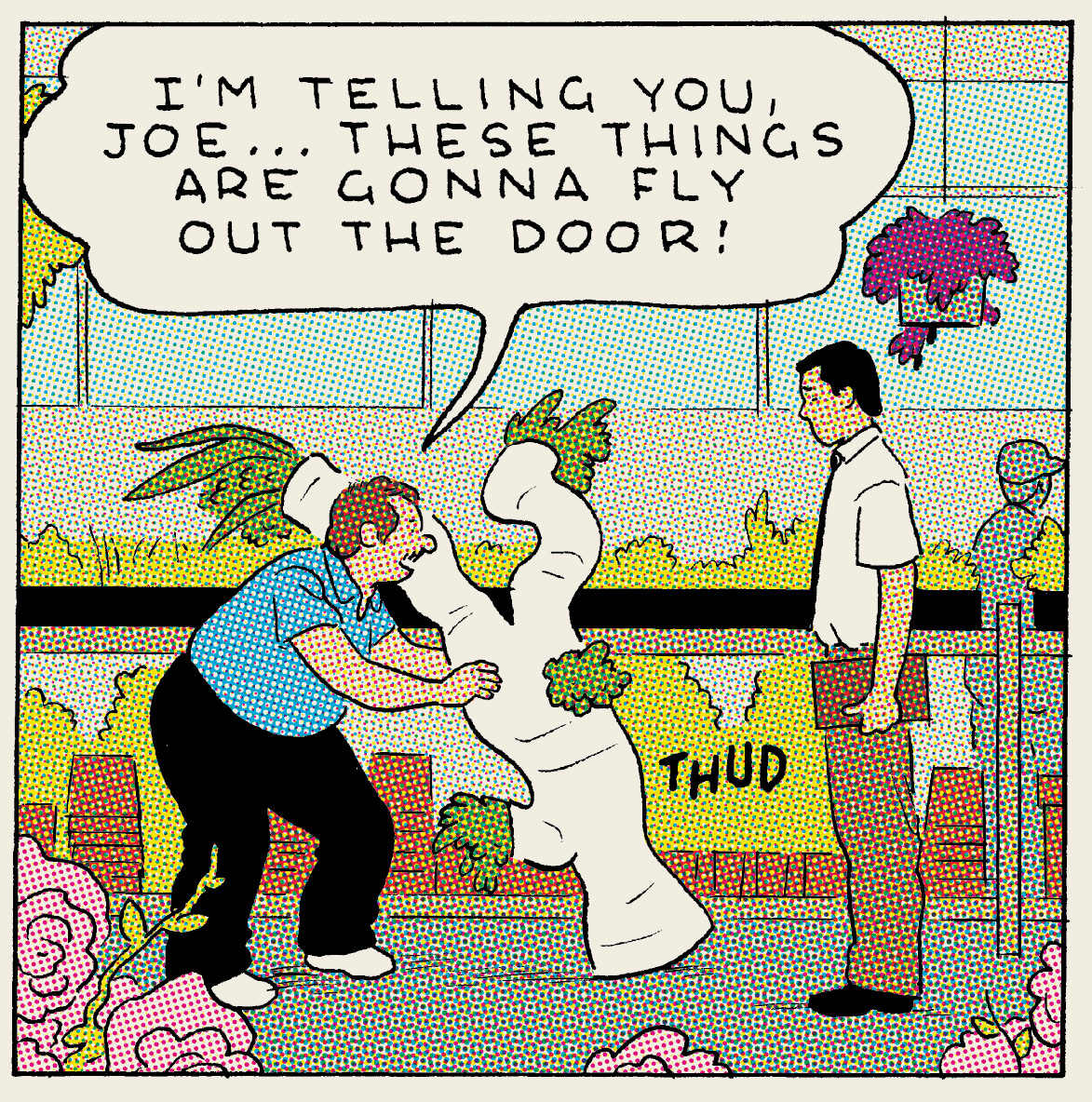

One last thing on the subject of evolution: I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the influence of my wife, Sarah, who’s been my most candid, consistent editor and critic for the past eighteen years. We’d known each other for a little while before she read any of my books, and when she did, she was complimentary, but I could tell she was sort of holding her tongue. I finally prodded her enough, and she hesitantly said something along the lines of, “It’s just…you’re so funny in real life.” I instantly knew what she was getting at. I’d been so determined to present myself as a “serious” and “alternative” cartoonist—pushing back on the then-common perception of comics as junk culture for kids—that I’d eschewed anything that reeked of the kinds of comic books I’d grown up loving: color, sound effects, thought bubbles, and, yes, humor. In general, I think I had muted the emotional tone of my stories, and that was probably a safe, contrived way of avoiding sentimentality. When Sarah encouraged me to allow more of my full personality into my work, and to not worry so much about presenting a “cool” demeanor, it felt like I’d been freed from some self-imposed shackles of pretension. I think, more than anything else, it was this mental shift that allowed me to enter a new, more expansive phase in my work. I’m certain that none of my books since Shortcomings would exist as we know them without Sarah’s profound impact on me, both as an artist and as a person.

This was very nourishing and inspiring and I'm of course thrilled to see your tools listed out. A drawing nerd's dream!

You answered my question (I’m the second one). Many thanks! And a big thank you for everything you’ve written so far and for opening yourself up for questions here. It’s been really great, interesting reading.

I don’t want to hog question-time here but another two questions from me, for if you run low on them in the coming weeks:

Do you have any how-to books for writing/cartooning/etc that you’ve found especially helpful or significant?

I'd like to hear your recommendations, if you have any, but I’m mostly asking just because I like how-to books in general and find it interesting to hear about what a favourite cartoonist might’ve spent time focused on. I know you’ve mentioned ‘How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way’ as a starting point but I was curious about what else there might’ve been along the way.

And my second question: Could you walk through your current technical process for illustrations, covers, etc? Are you someone that’s flipping and re-drawing again and again? Do you take photos of yourself in poses? I really love your line quality and I wonder what your thinking is about things there, if anything. Paper size too. I could be wrong (I'm just going by the odd 'for sale' page with measurements) but it seems like you're drawing a lot smaller than you used to. I like reading about that kind of stuff and I’m pretty sure I'm not alone there.