Q: At the end of The Loneliness of the Long–Distance Cartoonist, it shows you getting out of bed, presumably to begin this very work. You get a notebook out that is much like the design of this book, and begin working. Did you illustrate this book in a notebook or was it on more traditional sheets of paper?

I’ve been cagey about this in the past, but I guess now is as good a time as any to come clean. I wanted to create the impression that I drew the entirety of TLOTLDC directly into a Moleskine sketchbook, and that the published book was basically a replica of that sketchbook. But that’s not actually the case. Evidently, that would’ve been too easy and spontaneous for me, and I had to find a way to make everything more complicated.

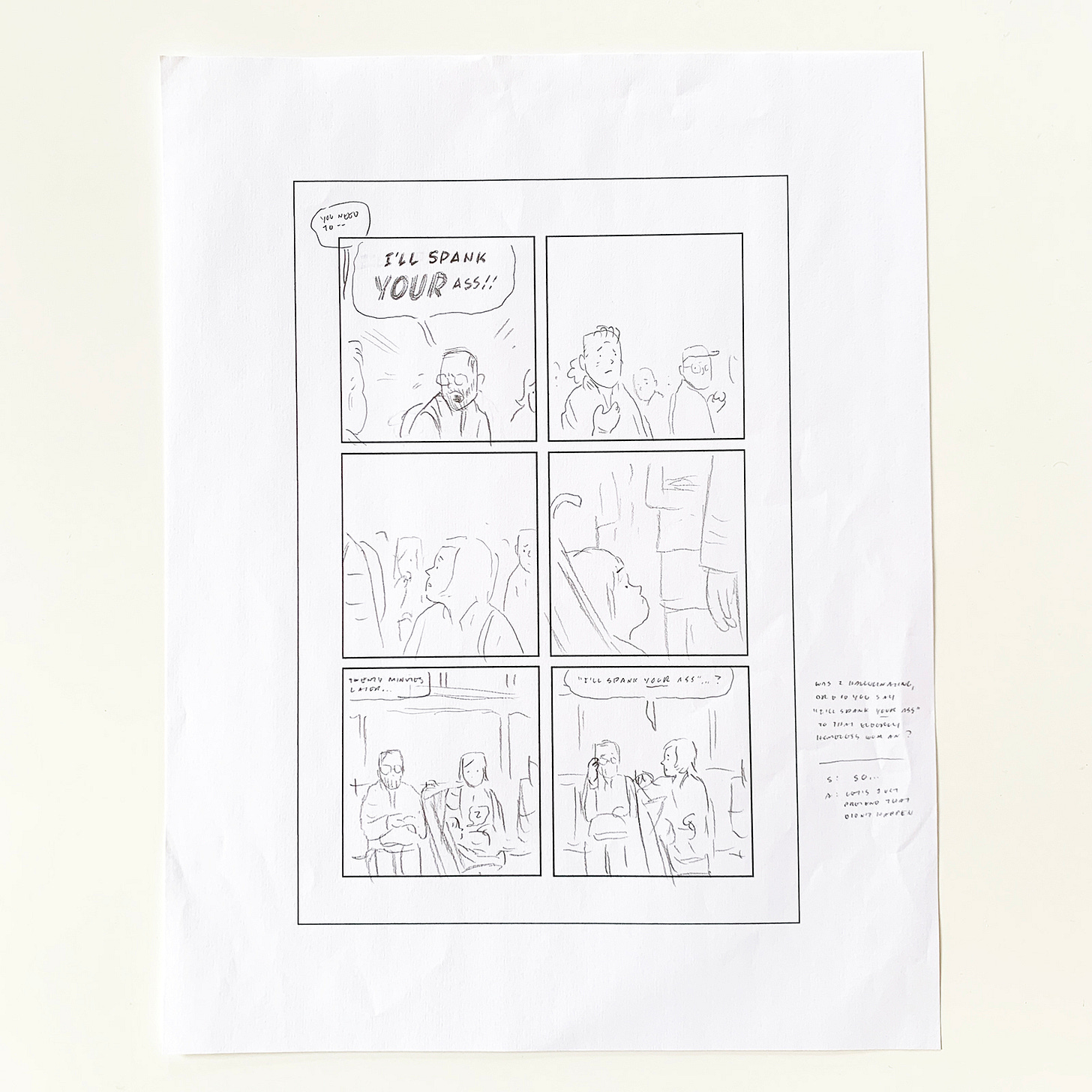

I did draw very rough versions of a lot of the anecdotes in a small “squared notebook,” but they were almost indecipherable to anyone other than me. It was just the quickest transcription of a real event, like the way someone might scrawl words in a diary meant for their eyes only. But the belief that no one would ever see this stuff was useful in that it allowed me to record some truly bizarre, mortifying moments—the kind of memories that are often buried or whitewashed by shame, and precisely the type of material that I wanted for this book.

When I decided to try to expand upon these scribbles and turn them into a book, I made a six-panel template in InDesign and printed out a big stack. And then I basically “wrote” the book on those printed pages, sketching out each panel very loosely in pencil, often making notes and trying out alternative ideas in the margins.

This was by far the most time-consuming part of the book’s creation, and there were multiple discarded drafts of every single page. It was tempting to work out some of the dialogue in script form on the computer, but for a book that relies so heavily on facial expressions, gestures, and timing, it felt necessary to do all the writing in the language of comics.

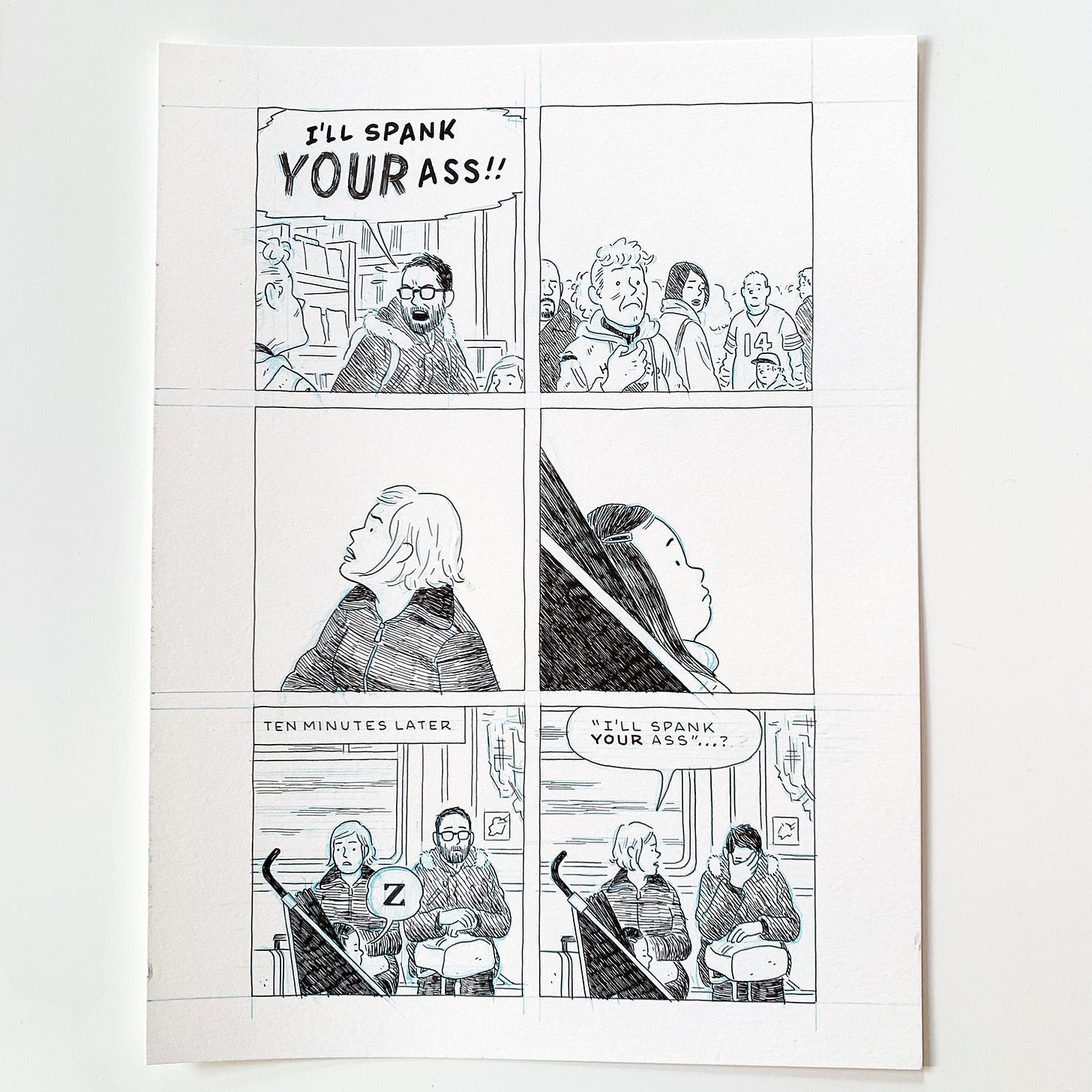

The act of translating a real experience into comics form is sometimes a harder task than you’d expect. For me, just getting the simple facts of the story transmitted to the reader was often surprisingly difficult. I could recall these incidents in my mind perfectly, but as is often the case with memories and dreams, I saw them from a first-person point of view. I had to re-imagine all of the material in a more objective, third-person mode, and that often entailed envisioning things (e.g. myself) that I couldn’t have actually witnessed. Similarly, everything about these anecdotes made perfect sense in my mind—any back story or scene-setting was self-evident to me—but would often require some explanation for anyone else. I had decided early on to not use narration in this book, so any necessary information had to be expressed through “present tense” images, dialogue, or thoughts. Most of the writing process was really just me struggling to translate something that could be easily explained verbally (e.g. “I lost my mind and yelled something insane at a frail old lady, and all of Penn Station fell silent”) into a sequence of clear, easily-digested panels.

The final pages were drawn on 9” x 12” Bristol board, using the tools mentioned in a prior post: a blue pencil, a Pitt artist pen, and a Tachikawa “school” nib.

Then I scanned these pages into the computer and placed them on top of a light blue grid pattern.

So there you go. A long, convoluted process designed to create the illusion of being quick and spontaneous. Advice to aspiring cartoonists: don’t do this.

Q: When looking at your posts that show your process of work, it would appear that you use blue pencil for sketching, ink over that, then color digitally. Why do you start traditional, then transition to digital?

I’m happy to answer this question, but as with my previous response, I intend this only as an explanation of my personal working methods, not as any kind of prescriptive advice. But you’re absolutely correct about my process for creating color images. It’s something of an analog / digital hybrid, in which I draw all the artwork with ink on paper, and then I create the color digitally (with a weird combination of Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign). Here’s an example from a recent illustration for The New Yorker.

You might be wondering why, in the 21st century, am I still drawing on paper? The simplest explanation is that I enjoy working with pens and pencils and paper, and for whatever reason, I find working on a computer to be a physically-taxing, eyeball-straining chore. Creating the line art is the most time consuming part of the illustration process, and I prefer to spend those hours hunched over my drawing board rather than staring into a screen. Also, over the years I’ve learned to draw in a physical, tactile way. The sensation of pencil, pen, and brush on paper is deeply embedded in my technique, and I delight in the unexpected marks that come from a slightly dry brush or a worn-down nib. I like being able to rotate the paper so that I can find the perfect angle for pulling a brush across the surface. As weird as it may sound, I enjoy making corrections by scratching away dried ink with an X-acto knife or brushing on layers of semi-transparent white paint. I know, I know…this can all be digitally replicated with incredible ease. Probably true, so let’s just say it’s an eccentric personal preference and leave it at that.

So then why do I create the color on a computer? This choice is based entirely on the end results I’m trying to achieve, as well as the current printing technology that’s used to reproduce my work. I want my artwork to have flat, mechanical-looking color, like the comics and illustrations I grew up studying. It might be different if I was aiming for a modeled, painterly result. In that case I could apply watercolor directly onto the line art. But ironically, a computer is the best tool for me to emulate the look of coloring that was created in the pre-digital era.

A few last thoughts about all this. Aside from the matter of personal preference, I think it’s worth mentioning that drawing on paper results in tangible artwork that can be exhibited and sold. I know that sounds like I’m stating the obvious (let’s spare ourselves any discussion of NFTs for now), but it’s something to consider. At the risk of sounding gauche, I think it’s important to share that I’ve made far more income over the years from selling original artwork than I have from publication fees, advances, or royalties. If money’s not a concern for you, or if you have a regular job and you’re just making comics as a hobby, then don’t worry about this. I understand that sometimes you need to just get the pages drawn, in as quick and easy a way as possible. But I can tell you that as a full-time cartoonist / illustrator with a family, art sales have completely saved my ass (and by extension, my family’s asses) innumerable times over the years.

Also, I got to bring my dad to a gallery show of my work here in New York before he passed away, and that’s an experience that means more to me than any time I might’ve saved by drawing on a screen.

"I'll spank YOUR ass" is my favorite scene from that book. Thanks for sharing!

Did not expect that ending. Very touching. I am loving this newsletter so much, I don't want it to stop.