Prose / 180 Degree Rule / Collaboration / Pacing / Endings / Moments / Dialogue / Phases / Shying Away / Realistic Drawing / Pressure

Q: When writing your stories, how much prose do you produce before beginning the thumbnails or sketches?

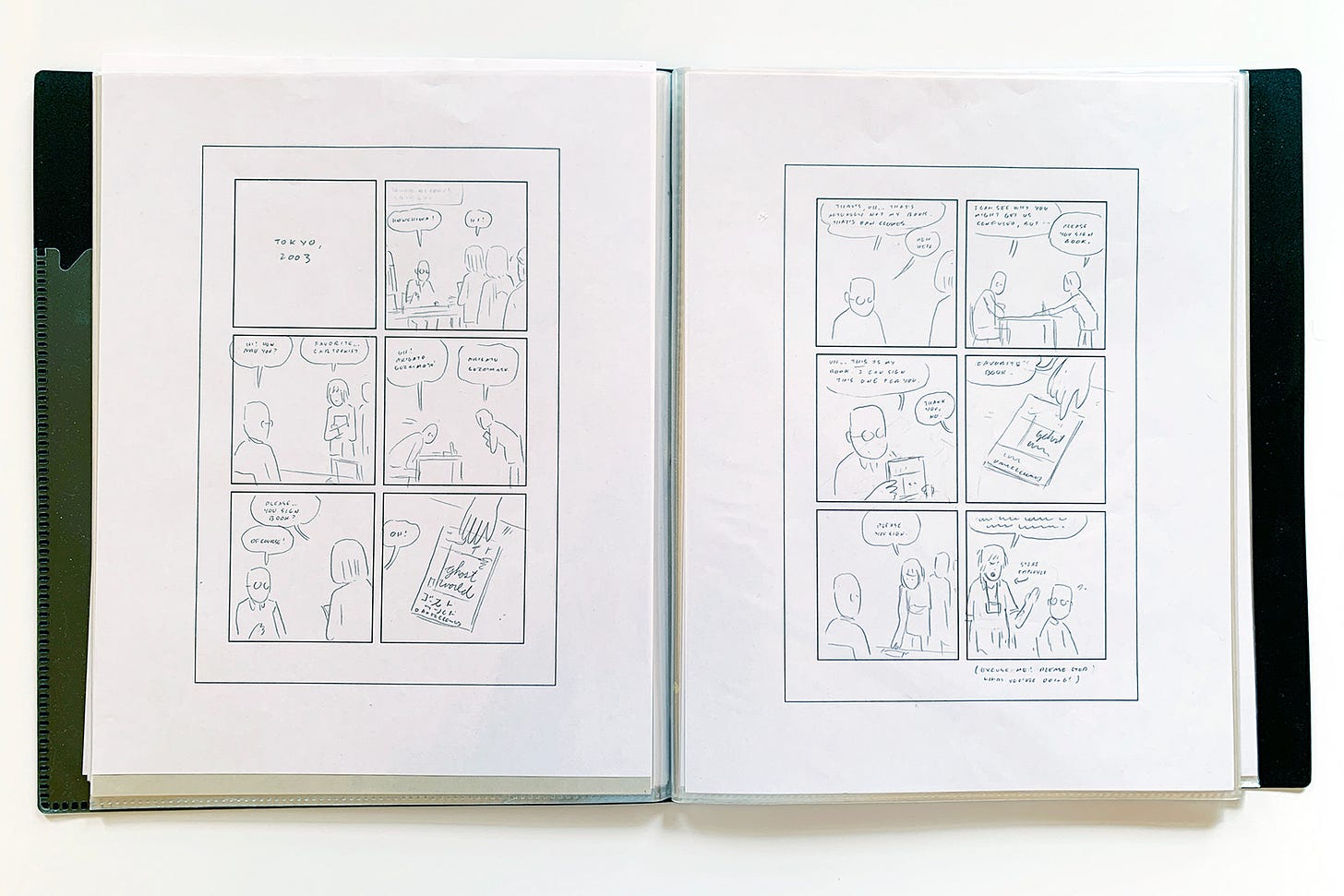

Almost none. As much as possible, I try to write comics in comics form, which allows me to think about the words and images simultaneously. This is how I’ve written my last couple of books: very rough pencil drawings on paper, arranged in an Itoya folder (plus a mountain of crumpled up “reject” pages on the floor).

Q: What is your approach on the 180 degree rule? Is it something you try to keep as much as you can, or is it not something you consider to be important at all?

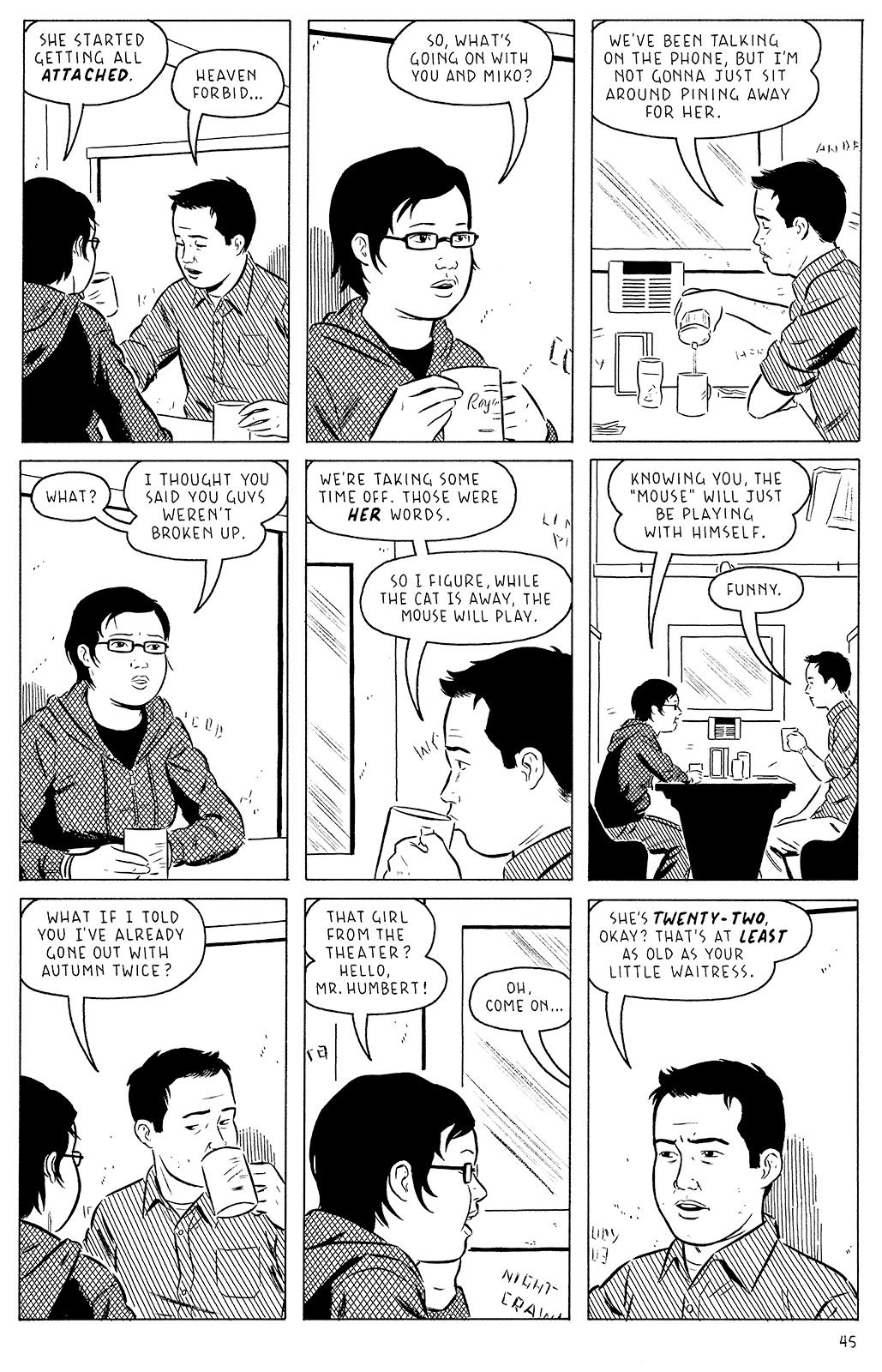

I don’t think about it consciously, but in my effort to make my comics as clear and readable as possible, I find I’m often intuitively obeying it. Sometimes, as in this page from Shortcomings, the setting basically imposes the rule.

Q: I can’t draw for shit, in part because of a neurological condition that causes my hands to constantly shake as if I were 90 years old. How does someone approach illustrators / artists / cartoonists when it comes to collaborating?

Sorry to hear about your condition. I’m not sure, but it’s possible that an agent or a publisher could act as a “matchmaker” and help pair you up with an artist. Feel free to identify yourself in the comments here, and if anyone is interested in collaborating, they can get in touch with you. Good luck!

Q: My question is about “pacing in comics.” What’s your process for “nailing down” the story’s pacing per page and panel? Do you go by story beats or information you deem important, or both?

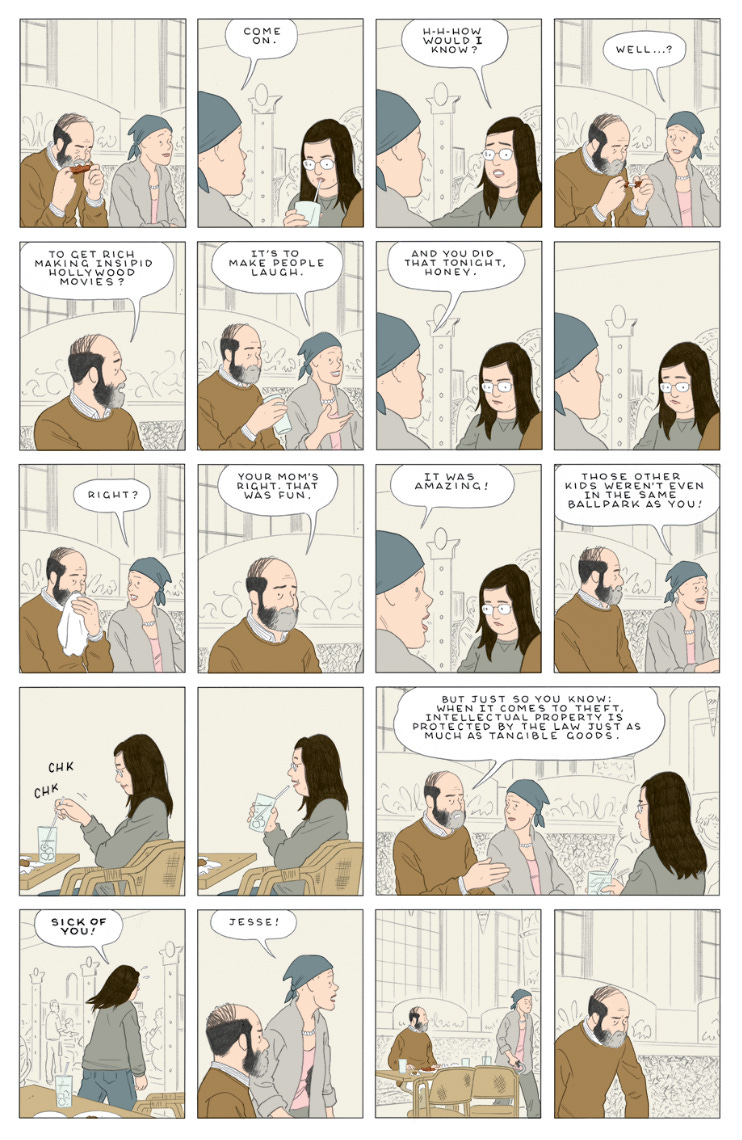

I usually just try to tell the story I have in my mind, and I keep editing and adjusting the rough draft until it reads the way I want it to. For this scene from Killing and Dying, for example, I imagined the conversation playing out in real time, and then tried to replicate that as best I could by breaking up the dialogue, expressions, and gestures into panels.

Aside from trying to make a scene feel natural and believable, the main thing I’m thinking about with regards to pacing is holding the reader’s attention. I’ve found that too much text—regardless of how beautiful it may be—will cause a reader to skim or skip ahead. Of course there will always be exceptions, but for a scene like this one—in which I’m basically trying to make the reader feel like they’re sitting there with the characters at The Cheesecake Factory—I find that simple, easily-digestible panels with a sentence or two of dialogue work best. It might seem more economical to cram a lot of dialogue into one panel, but not only does that tend to overwhelm the reader, it gives the comic a stilted tone, as if the characters are frozen in time while reciting their words.

Q: I was wondering how often you explicitly think through how and why an ending works, versus going off a more intuitive feeling?

I don’t think the two approaches you describe are mutually exclusive. I give a lot of thought to my endings, but I also try to arrive at them intuitively. It’s hard to give any clear advice about this, because it seems contradictory to say, “You should really think carefully about the ending, but don’t think about it too much!” Maybe the best way to describe my approach is that I try to use my conscious mind to reject or edit the bad ideas, but I allow my subconscious mind to surprise me with the good ones.

There’s a certain kind of ending that I love, and it’s hard to describe, but it usually contains a mixture of surprise, mystery, simplicity, and unspoken feeling. Some of my favortie short stories by John Cheever, Raymond Carver, and Otessa Moshfegh are good examples of this. The films 45 Years and The Ice Storm come to mind. Or the original version of The Office. I could watch those a hundred times and still feel chills when they cut to credits. I can’t really articulate why those endings have that effect on me, but that sensation is something I’ve thought a lot about, and have probably been chasing my whole career.

Q: What are the most reliable methods you have found to select the moments that must be conveyed in a story, and to compose them in such a way that it affects your artistic vision?

I’m not sure I completely understand your question, but I think you’re assuming that I have a more strategic, methodical approach to writing than I actually do. I often start with an idea or a character or a scene, and then just let it slosh around in my brain for a long time, often while doing other things. If I do this for long enough, I’ll eventually arrive at a rough version of the complete story in my mind, and then I can finesse that to a degree as I start sketching on paper. But I usually don’t have an articulated reason or explanation for why I picked each moment. I think you can usually tell when something’s been written that way, and it doesn’t feel very lifelike.

Q: How do you approach writing dialogue? I have a hard time making dialogue sound unforced / genuine and move the story along.

I don’t mean to be reductive, but I think you just need to work on it—even if it means focusing on one sentence at a time—until it “sounds” the way you want it to. If it makes you feel any better, this is something that I struggle with all the time. As I described in a previous post, I do a lot of work to make things seem like they were effortless! If you’re critical of the dialogue you’ve written in the past, then it means you’ve already developed your own personal “bullshit meter.” That’s a big step: you’re aware when something isn’t right. The next step is to fix it, and the only way to do that is to try different versions of each piece of dialogue. Sometimes this can mean something as slight as changing a single word or replacing two words with a contraction. I find it useful to mentally inhabit the character, almost like you’re an actor taking on that role, and then just speak / write in that voice. Maybe even more importantly, I’ve found it helpful to let characters and stories exist and evolve and reveal themselves in my mind for as long as possible before committing them to paper. The better I know the character, the easier it is to put words in their mouth.

Q: Sometimes it takes me forever to finish a comic because I’m constantly going through phases of “this is good, ppl wanna read this” vs “wow my stuff is trash and no one will want this.” Do you get phases like this? How do you stay motivated?

I think you’re essentially describing my base-level mental state while making comics. I honestly can’t imagine going through the process of making a book with unwavering confidence and self-satisfaction. It’s difficult, but I think the key to managing these kinds of “bi-polar” thoughts is to be as objective as possible. Make sure you’re not deluded in either direction, and try to evaluate your work in a way that’s critical but not defeating. I also think it’s useful to not obsess too much about how people will receive the work, and to instead focus on just making it as satisfying to you as possible.

Q: Do you ever find yourself shying away from a story you’re interested in because it’s either too challenging / controversial, too far from what you think your audience is interested in, or even too close to another author’s territory?

I know the admirable answer here is “no,” but the truthful one is “yes.”

Q: Do you have any advice about how to draw somewhat realistic characters from imagination? I spent many years going to life drawing three times a week, then studied anatomy for about a year, and still, if I try to draw a figure from my head, the result looks like the demented scribbles of a child. Is there any way out of this?

I think the unfortunate truth is that most people are just not able to draw the way they’d like to. I’m usually disappointed with my own drawings, and every single one of my cartoonist friends has expressed similar sentiments at some point. The good news is: you’re interested in cartooning (I assume, since you’re writing to me) and not photorealistic portraiture. There’s a great history of comics in which the drawings are stylized, simplified, exaggerated, etc., and to my mind, those types of comics read much better than the ones that look like they were drawn from photographs. I’d recommend embracing and exploring the natural idiosyncrasies of your style, and perhaps focusing more on the content of your comics, not the level of slickness or realism in the drawings.

Q: I’m an emerging cartoonist working on my first book. The pressure is killing me and dampening my natural weird story ideas and I worry the raw energy of my drawings is being lost, too. Any tips on how to keep anxiety at bay and get back in the zone?

I know very well the anxiety you’re describing, and I’m always struggling to find ways to minimize its presence in my own work process. For me, that often means working in secrecy. Instead of starting with a “pitch” to my publisher, I began working on my last book without telling anyone. I felt like I was free to explore and to make the book exactly as I wanted it, and if it was horrible and I scrapped it, no one would be the wiser. I also didn’t immediately take an advance or commit to a due date, both of which have been the source of great stress for me in the past. Of course nothing will completely eliminate feelings of pressure or anxiety, but I’ve found it helpful, as much as possible, to trick myself back into the mindset I had when making comics was just a hobby. It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that this is something we started doing because it was fun.

I love this: "Maybe the best way to describe my approach is that I try to use my conscious mind to reject or edit the bad ideas, but I allow my subconscious mind to surprise me with the good ones." It's true... you have to use both.

Splendid and very insightful read Adrian. Loving the part where you mention the importance of exploring your drawing style.